The checklist manifesto by Atul Gawande

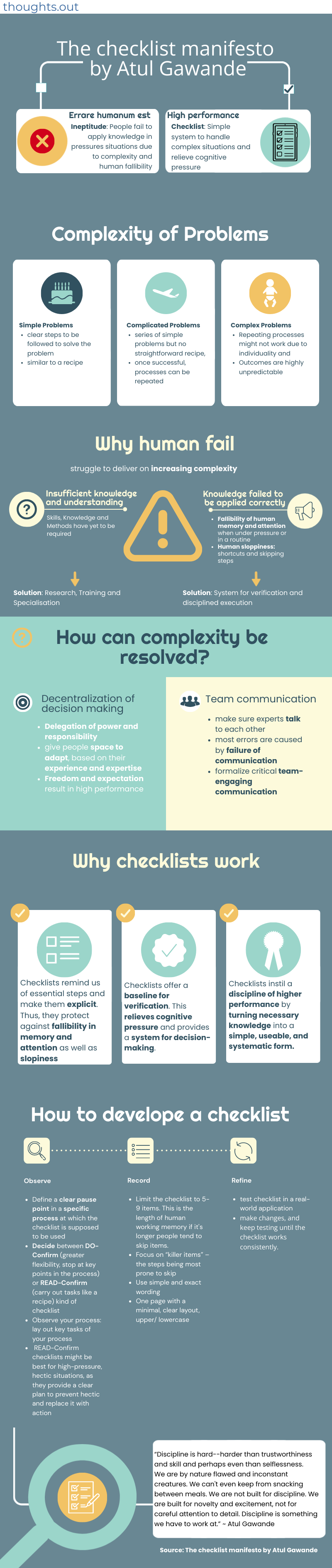

Errare humanum est - but with a checklist in place, human has a baseline for verification and can develop a discipline of higher performance.

If there was a pill that would enhance your baseline performance without touching your abilities or skills, would you not be prone to take it? Simply getting better results without having to train harder or study more would leave any supporter of the maximum principle excited. Maybe it would even be considered cheating. But this pill does exist – it’s called a checklist.

Errare humanum est – Failures are part of human nature. Some things we want to do are simply beyond our capacity. Even enhanced by technology, our physical and mental powers are limited.

In realms of humanity's greatest achievements, like building skyscrapers, flying planes, and saving people in life-threatening situations failure comes in two shapes:

- Ignorance: We might err because our level of understanding of a certain topic is not yet sufficient, and more research is to be conducted.

- Ineptitude: There is profound knowledge, yet people fail to apply it correctly

Knowledge and sophistication have increased remarkably across our realms of endeavor. Yet experienced, well-trained, and capable people make avoidable make mistakes every single day.

Especially when done in life-threatened situations, those failures seem to carry emotional weight. Failures of ignorance can be forgiven. If knowledge about best practices is absent in given situations, we are happy to have people simply do their best. In contrast, if the knowledge exists and is not applied correctly it is difficult not to be infuriated. But the judgment often ignores the reality of complexity – of how extremely difficult the job is.

However, the capability of individuals is not a limiting factor as training in most fields follows the highest standards. But failures remain frequent and persist despite remarkable individual competency.

It is time for a paradigm shift. The solution lies in something incredibly simple: A checklist.

Checklists improve the baseline of performance without adding any skills. Making steps explicit and easy to follow through like a recipe, important steps are hardly missed. The use of checklists provides a framework for verification and instills a kind of discipline of higher performance. Being a simple, straightforward tool almost every area of life can benefit from a checklist.

In the book “the checklist manifesto” the author Atul Gawande portrays his journey from his attempt to reduce human failures in surgery. Reaching out to other fields like the building and flying industry, where high standards of excellence had already been established he learned about the values of an incredibly simple tool- the checklist. He tells his story about adopting and refining his surgery checklist and successfully preventing failures in his practice.

The Problem of extreme complexity

As the author being a surgeon illustrates, many realms have become the art of managing extreme complexity. This most notably applies to medicine, but also the construction and flying industries are remarkably complex. For medicine, in particular, this complexity comes in various types of diseases which oftentimes interfere with each other having patients react individually from case to case. When lives are on the line medical care succeeds only when specialists hold the odds of harming low enough for the odds of doing good to prevail.

This is the fundamental puzzle of modern medical care: you have a desperately sick patient and to save him you have to get the knowledge right and then you have to make sure that the 178 daily tasks that follow are done correctly – despite the tremendous pressure in the situation. Absolute professionalism is expected.

Results of recent ever-refined specialization have been a spectacular improvement in medical capability and success. However, research has shown that at least half the deaths and major complications are avoidable in surgery. The knowledge exists but mistakes are still made - despite the era of super specialization.

The checklist

On October 30, 1935, the first introduction of the Boing Model 299 was highly anticipated. Sleek and impressive with a 103-foot wingspan and four engines, rather than the usual two the plane was substantially more complex for pilots to handle than the previous aircraft. The first flight ended with a crash due to “pilot error” - despite the pilot being one of the most experienced. The complex airplane was described as “too much airplane for one man to fly”.

As it was hard to imagine gathering more experience than the victim, the Model 299 pilots were not required to undergo longer training. Instead, a pilot’s checklist was created. Using a checklist for take-off no more occurred to a pilot than a driver backing a car out of the garage back at the time. But flying this new airplane was too complicated to be left to the memory of any one person, however expert.

The checklist was simple and concise with step-by-step checks for take-off, landing, and taxiing. These steps were partially trivial like checking if the doors are closed. But ultimately, with the checklist in hand, the pilots managed to fly the aircraft a total of 1.8 million miles without one accident. The very model became an important factor in the Allies' victory over Nazi Germany.

Analogously, much of our work in modern fields has become too much airplane for one person to fly. Substantial parts of what software designers, financial managers, or clinicians do are now too complex to be carried out reliably from memory alone.

In a complex environment, experts face two main difficulties:

- The fallibility of human memory and attention especially when carrying out mundane routines that are easily overlooked or in pressure situations. Missing one key thing in an all-or-none process, you might as well not have made the effort at all.

- Human sloppiness: People can lure themselves into skipping steps even when they remember them as certain steps don’t always matter. “This has never been a problem before” they might say. Until one day it is.

Checklists seemingly protect such cases. **They remind us of the minimum necessary steps and make them explicit. They not only offer a baseline for verification but also instill a kind of discipline of higher performance. **

The resulting higher standard of baseline performance had been surveyed in tackling central line infections by Peter Pronovist: The ten-day line infection rate went from 11 percent to zero. The likelihood of a patient enduring untreated pain was reduced from 41 percent to 3 percent with the proportion of patients not receiving the recommended care dropping from 70 percent to 4 percent. Consequently, the average length of patient stay in intensive care dropped by half. Great results for a simple tool.

The end of the master builder

There has been proposed distinction among three different kinds of problems in this world:

- The simple: baking a cake from a mix using a recipe

- Complicated Problems: Sending Rocket to the moon. Might be broken down into a series of simple problems without a straightforward recipe. Success requires multiple people, teams, and specialized experts

- Complex Problems: Like raising a child, once you land a rocket on the moon you can repeat the process and perfect it. Raising children is highly unique, the individuality of each child adds complexity. Expertise is valuable but most certainly not sufficient. The outcome of complex problems remains highly uncertain.

Reaching out to the construction industry, which is a similarly complex field of profession, the fundamental questions remained for Gawande:

- How can be made sure, the right knowledge is at hand?

- How can be made sure knowledge be applied correctly?

Skyscrapers, stadiums, hotels, and other buildings the likes are incredibly complex. Every building is new and individual in ways both small and large – they are complex as a result there is no textbook formula for the problems that come up. Yet we manage to put them up safely – thanks to the variety of specialized domains working together. Various forms of expertise are fragmented into multiple divisions ranging from crane operators to finish carpenters- an interplay of specialists.

How can a building come together properly despite the number of considerations – and even though a project manager could not possibly understand the particular of most of the tasks involved?

A checklist provides the solution – lots of them are included in a scheduling program and as each task gets accomplished a checkmark is put in based on the respective supervisor's report. Thereby a succession of day-by-day checks that guide how the building is constructed and ensure that the knowledge of hundreds is pitted to use in the right place at the right time in the right way.

Handling uncertainty in complex situations

There is always a risk of unforeseen events. The way the project managers deal with the unexpected and the uncertain was by ensuring communication of the domains involved. With a checklist including communicational tasks, they made sure the experts spoke to each other.

The experts could make individual judgments but had to do so as a part of a team that took one another's concerns into account, discussed unplanned developments, and agreed on the way forward. While no one can anticipate all the problems, they could foresee where and when they might occur. The checklist therefore detailed who had to talk to whom, by which date, and about what aspect of construction – who had to share or submit particular kinds of information before the next step proceed.

Anything can go wrong – that’s the nature of complexity, but with the right people talking things over as a team rather than as individuals, serious problems could be identified and averted. In the face of the unknown, they believed in the wisdom of the group, the wisdom of making sure that multiple pairs of eyes were on a problem and letting the watchers decide what to do.

We allow buildings of high difficulty to design and construct to go up amid major cities of thousand people inside and countless more living and working nearby. This seems risky and unwise. But we allow it based on trust in the ability of experts. They know better than to rely on their abilities to get everything right. They trust instead in one set of checklists to make sure that simple steps are not missed or skipped and, in another set, to make sure that everyone talks through and resolves all the hard and unexpected problems. The biggest cause of serious error in this business is a failure of communication.

The success of clear communication is demonstrated by the countless builds around the globe. The low percentage of serious failures in this industry provides proof - Checklists work.

The idea

As Gawal discovers, the underlying idea of dealing with an unanticipated anomaly in construction is to push the power of decision-making out to the periphery and away from the center. You give people the room to adapt, based on their experience and expertise. All you ask is that they talk to each other and take responsibility. Complexity requires delegation of power and responsibility.

Under the conditions of true complexity – where the knowledge required exceeds that of any individual and unpredictably reigns – efforts to dictate every step from the center will fail. People need room to react and adapt. They require a seemingly contradictory mix of freedom and expectation – expectation to coordinate and measure progress towards common goals.

Under conditions of complexity not only are checklists of help; they are required for success. They establish a benchmark to produce results of consistent quality over time. However, not everything can be anticipated and reduced to a recipe. There must always be room for judgment, but judgment aided – and even enhanced – by the procedure.

The First Try

By the time recent developments of global surgery had exploded up to 230 million major operations annually in 2004 with rising trends. Most of the time a given procedure does just go fine – but often it does not: estimates of complications rates for hospitals range from 3- 17%. Worldwide, at least seven million people a year are left disabled and at least one million dead.

Improvements in global economic conditions in recent decades had produced greater longevity a therefore a greater need for essential surgical services ranging from cancer treatments, and broken bones to disabling kidney stones and gallstones. Remedying surgery as a public health matter had come to the close attention of the WHO and Gawande was enlisted to participate in a committee to improve surgery outcomes in developing countries.

Here, Gawande experienced various surgery problems in hospitals worldwide. From problems with anesthesia due to low respect, most surgeons accord aesthesis to inadequately maintained surgical devices - the situations in hospitals were highly individual. A profound yet simple easy-to-adapt solution had to be found.

Interventions were required to have widely transmissible benefits with measurable effects. In other terms: High ROI (return on investment), Leverage, or 80/20 Principle had to be established. The key point is to have simple, measurable transmissible requirements.

Exploring similar public health studies on the deep and multifactorial roots of the problems, they found the most impactful approaches to be bottom up- simple and with specific instructions. Lack of hygiene due to poor water and sewage systems had been resolved by plain soap as a behavioral-change delivery device along with clear hand-washing instructions. The soap had become leverage.

Much similarly, checklists were thought to be equally simple yet highly effective in terms of the requirements. There are four major reasons for complications in surgery: infection, bleeding, unsafe anesthesia, and the unexpected. In the matter of the first three, science and experience exist and have provided straightforward and valuable preventive measures. Failures in these fields are most certainly due to ineptitude – a classic case for a checklist. The latter can be resolved by effective team communication.

To foster teamwork, the psychological effect of disengagement studied by Brian Sextion as the main driver for poor communication resulting in a lack of accountability and failures had to be faced. Proper communication and engagement had significantly been shown to improve the ability of surgeons to broadly reduce harm to patients. Consequently, there had to be a step employed in the checklist, making sure names and potential concerns were mentioned at the start of surgery.

The checklist factory

Good checklists are precise and efficient, to the point, and easy to use even when situations are most difficult. They try not to spell out everything, they include the most critical and essential steps.

How to create a good checklist

- Before you start: Observe the process

- Define a clear pause point at which the checklist is supposed to be used

- Decide between DO-Confirm or READ-Confirm kind of checklist

- Do-Confirm: perform tasks from memory then pause to check, greater flexibility in performing tasks while nonetheless having to stop at the key points to confirm that critical steps are not overlooked.

- READ-Confirm: Recipe like carrying out tasks as you check them off

- Observe the process: lay out how you do it

- READ-Confirm checklists might be best for high-pressure, hectic situations, where the brain switches to survival mode which might be challenging for performing tasks from memory as in a DO-Confirm checklist. They provide a clear plan to prevent hectic and replace it with action

- Creating the Checklist: Record your process

- Limit the checklist to 5-9 items. This is the length of human working memory if it's longer people tend to skip items.

- Focus on “killer items” – the steps being most prone to skip

- Use simple and exact wording

- One page with a minimal, clear layout, upper/ lowercase

- Improve checklist in iterations: refine the process

As real-world applications, checklists must be tested. First draws often fall apart, one needs to study how, make changes, and keep testing until the checklist works consistently.

Checklists are simple and quick tools aimed to buttress the skills of expert professionals. Checklists translate the necessary knowledge into simple, useable, and systematic form, but are no how-to guides by any means.

The test

With sufficient background knowledge about checklists derived from various industries where checklists had been an integral success, Gawande went into the field. A surgical safety checklist had been created. It is comprised of tasks to perform before induction of anesthesia before skin incision and before the patient leaves the operating room. Going for a Do-Confirm Approach due to greater flexibility all critical steps were included. This ensured knowledge was applied correctly, no steps to be skipped, and critical team-engaging communication.

The checklist was introduced after passing 19 refining tests in 8 hospitals with different settings. The first results were promising: Various problems had been prevented such as problems with antibiotics, equipment, and overlooked medical issues. Overall, going through the checklist was said to help the staff respond better to later complications.

93 Percent supported the use of checklists when conducting an operation.

The hero in the age of checklists

Checklists seem to be a simple and effective solution to human ineptitude, yet there is resistance hampering their adoption. If a new drug or surgical robot was invented that could equally cut down surgical complications with anything remotely like the effectiveness of a checklist, there would be television ads with celebrities and stocks of the company skyrocketing. Something so simple as a checklist seems to threaten legacy.

Checklists also can be used in finance. When investors aim to buy coca cola before everyone realizes it is going to be coca cola the “cocaine brain”-the phenomenon is a serious challenge. Neuroscience research has found the prospect of making money to stimulate the same primitive reward circuits in the brain like cocaine. Investors must become systematic to damp down the cocaine brain. Here, checklists prevent cutting corners in situations of high excitement. Complexity considering various features of a company can easily be overlooked, even without a cocaine brain. Checklists help with the systematization of this complex world. With a good checklist in hand, decisions, as well as human beings, are able can be made.

This is the power of systematized decision-making. The example of the US Airways flight 1549 and its emergency landing on the Hudson River, which was due to the pilot checklist, rather than a single heroic victory of the captain provides yet another proof of efficacy.

There are at least three elements all learned occupations have in common:

- Selflessness: responsibility for others

- Skill: aim for excellence in knowledge and expertise

- Trustworthiness: responsibility for personal behavior towards our changes

- Aviators: discipline following prudent procedure and functioning with others.

When dealing with overwhelming complexity we need a system to handle it. Thus, Checklists provide systematic support for discipline as a baseline for verification.

The save

After improving the checklist and continuing to see positive results, Gawande still had some reservations. He was not fully confident about the checklist as a tool for surgeons until this very checklist saved his patient’s life. Making him set aside extra units of packed red cells for “just in case”- scenarios the patient could be kept alive during a serious complication.

Gawande tasted his own medicine and became a firm believer.